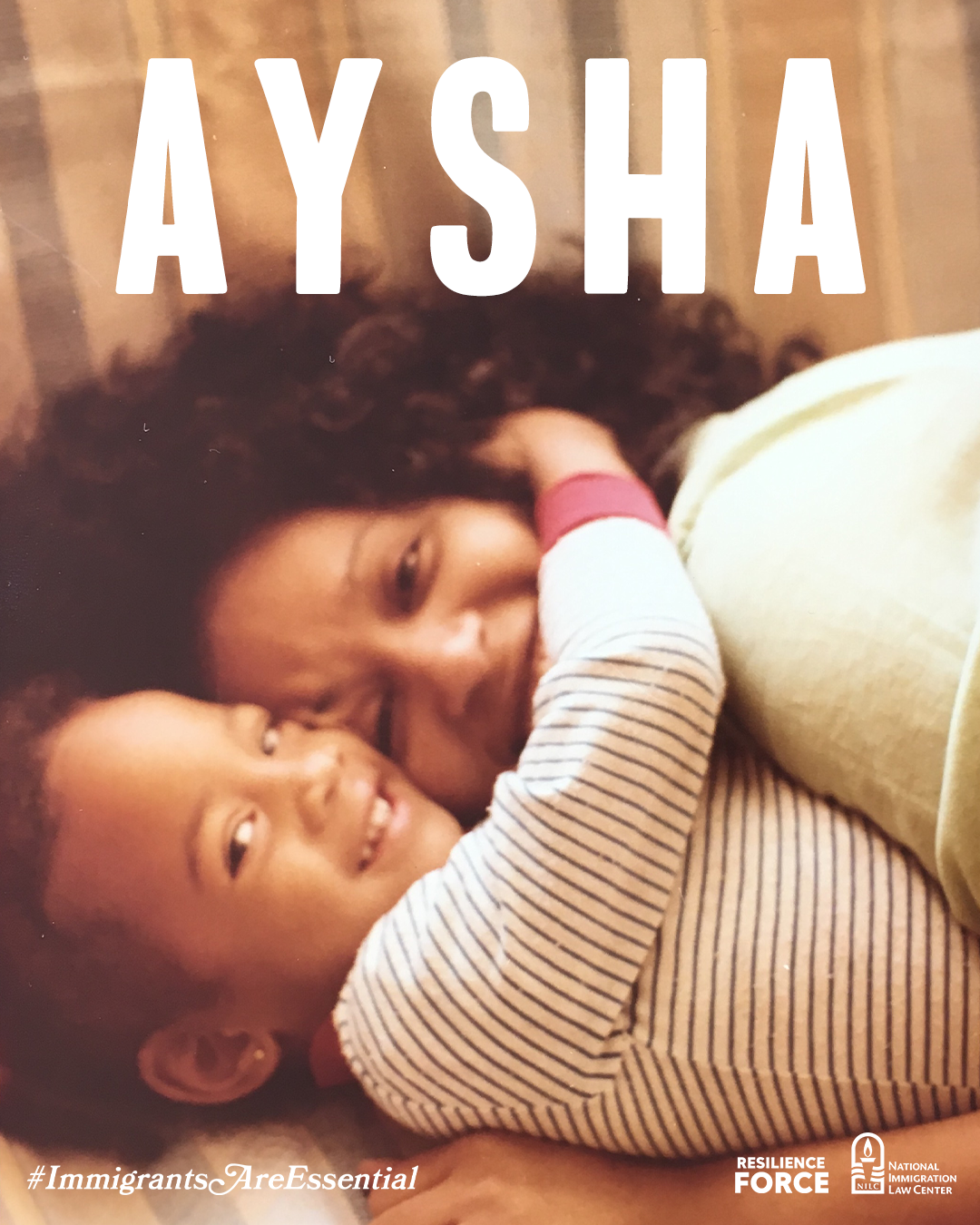

Aysha

In December, Kaiser physician and medical school instructor Dr. Aysha Khoury went viral on Twitter when she shared that her school Kaiser Permanente School of Medicine suspended her from teaching in August after she led a discussion around racial disparities and bias in health care with her students. On December 31st Dr. Aysha’s Khoury’s learned that her appointment would not be renewed after January 31.

Dr. Aysha Khoury: I knew I wanted to be a doctor since 5th grade. I knew in 11th grade that I wanted to teach. I did a second residency in public health and preventive medicine because medicine is so much bigger than treating one person at a time. When I completed that residency, the Kaiser region in Georgia had this new model of creating an observation medicine space that was completely outpatient. When you walk into it it looks like a small community hospital, but there's no hospital above it. This gave me a chance to talk with my patients and not be rushed. It was also very clinically challenging. And what was really great is that I got to precept students from Morehouse School of Medicine, my alma mater, in that space. So it was really just a wonderful combination of worlds. Then the school opportunity came and I was recruited as faculty for the Kaiser Permanente Bernard J Tyson School of Medicine.

Q: That sounds like it's been a long journey to reach this point and now you're in the midst of this new challenge, of entering a new space and speaking your truth and naming the racism that you've encountered and continue to encounter in the medical field.

Dr. Aysha Khoury: Those are not easy moments. It's still very difficult. On August 28 moderators for the inaugural class of the Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine were supposed to lead a discussion on bias and racism in medicine. I grew up in the US. I am a Black woman with the lived experience of growing up in America. There are some really incredible stories from throughout the diaspora; each is unique. I can separate my cultural background with elements from Trinidad and elements from Sierra Leone from my lived experience of a Black American woman. This is almost a “triple consciousness”. My experience as a Black American woman and physician is what I brought to the classroom. I moderated a discussion with students and shared some of my observations and lived experience. The class was very powerful. I think the support of the students from that discussion and the student body who rallied around me to bring me back to the school really underscores that. But within nine hours of the class I was suspended. I received a call from the Senior Associate Dean of Academic and Community Affairs to say that my teaching privileges had been revoked. I waited for them to do an investigation and one month went by, and one and a half months went by, and finally I was at least able to see patients again. Month after month of me feeling like, “Okay at any moment now I'm going to teach” passed by. And ultimately, I was fired.

I like how you phrased “named racism.” As part of my experience, and to be Black in America, and especially to grow up in the South, you're very aware of your racial identity in the United States. I've had experiences where the chief of a department has touched my hair in a meeting. I've had experiences where my residency advisor told me I wouldn't pass my boards. What I think is so hurtful about the situation with KPSOM is the values of the school have been betrayed and I bear the brunt of that.

Another thing that is so hurtful is the silence: the silence of people who you think are at the school for the same reason, so you would think would be motivated to speak up about this. And the folks who do are Black for the most part and the others who do are people of color. Even though this has been such a long journey, there have been so many layers to it and each layer just feels more painful than the last. My last official day as faculty was January 31, so this is still fresh. But there was still some part of me that was still thinking, “My colleagues are going to call.” While I was suspended, we were told we couldn't reach out and talk to each other. So I was still expecting I was going to get a call. I can't divorce a tolerance for racism from an act of racism. I find that really very difficult.

Q: Listening to you speak, I feel my own body responding to the grossness of the situation and that you had to experience that, and the loneliness of that experience I sense deeply in your words too.

Dr. Aysha Khoury: It's a very isolating experience, because on the one hand, I have amazing friends. I have two girlfriends in particular. Both PhDs. Both very grounded in faith. We have prayed and laughed and cried with all the beauty of the Black church experience with almost daily texting. My closest family are my dad and my brother and they've really helped me.

And then I went on Twitter. I’d had a session with my pastoral counselor and he said something to the effect of, “Aysha, we don't always understand the weight of our stories.” I had maybe 20 followers on Twitter. I put it out there. I wrote this thread. I put some of my life into the world, and I did not expect the way the world answered back. The support has been amazing because the recent election showed us that while

the majority of people might share a common interest and values, almost half the country has a tolerance for racism, sexism, queerphobia, and xenophobia.

What still blows my mind is the number of people who've reached out to tell me of their experiences of racism in medicine. And these are not just Black women. The majority of the stories have been from Black women, but these stories are also from Black men, Latinx, and Asian men and women. From trainees. From students. From people who have more clinical experience than I do. There are some white women who've spoken up on behalf of something that they've seen and were reprimanded. The anguish and the commonalities of these stories are horrible.

I still think about the eight students who made up my small group. I think about them almost every day. I had a very diverse class. It was wonderful. I cannot think of myself as an educator and think of those students and only look at my part in helping them was to pass an exam, because if I can't make it so that they're able to thrive in medicine, I feel that I failed. For the school to have done this to me with so many witnesses and not even, it seems, to take into account the effect that they've had on their Black students, I mean, it's shameful.

Q: I think about and imagine that you've had many people shape your life. Many teachers and many people who have made you the person you are today. One of the beautiful things about being an educator is that you got to continue that lineage.

Dr. Aysha Khoury: I think about my ancestry. Not only biologically, but also on the shoulders of the educators that I want to stand on. I moved to the States when I was eight from Toronto. I was there for six years, but in Sierra Leone in West Africa for two years. I remember my teacher Mrs. Palmer. I remember how earnest she was in ensuring that we learned. I remember Sr. Anna Kearns in a parochial school in the West end in Atlanta. She was the tiniest white woman with a perm that was a bit trimmed down on the sides. Oh, she was super cool. She had more energy than anyone in the sixth grade class. She had a Black Jesus with an Afro. I hadn't seen anything like that before. But the students were all Black and she just had such an enthusiasm for us. She was also dedicated to us being proud of who we were. I don't think a lot of people have examples of that especially across this racial divide that we find ourselves in in America. She was so amazing. She's just one of those people who I wish I could have gotten to say “see what I did”.

Dr. Aysha Khoury: My family’s story is not just one generation of immigration. It's two generations on both sides. My mother's side is from Trinidad and from Kashmir on my grandfather's side. Kashmir is a disputed territory that has been experiencing a lot in the past 12 months. On my mother's mother's side, there’s some Spanish heritage and some enslaved African heritage, I believe from Angola. My father's father came from Lebanon. Khoury is a very common Lebanese name. He and his father left Lebanon to go to the Canary Islands and then my great grandfather died. We don't know how he died. But he died, leaving my grandfather homeless. And he was somewhere between 13 and 16. He was kind of a scrappy kid and did what he needed to do to survive and was an immigrant selling souvenirs tourists. You see this today when you visit places like Paris or Rome. Eventually another Lebanese person takes him under his wing and they immigrate to Sierra Leone. My grandfather ends up making a life there. My grandfather was a “white” Christian man and he married a Black Muslim Sierra Leonean woman. They had a ton of kids. Many people from my father's generation moved to the UK, USA, or Canada. I have an aunt

who got a scholarship to McGill University in Toronto, and this started the migration of my aunts and uncles. This is how my father ends up in Toronto.

My father raised my brother and me and he leaves Toronto to be with his family, who were in the States. I saw my father work all his life. Growing up my father worked seven days a week. He had a regular job during the week and then on the weekends he refereed soccer matches. He was very dedicated to ensuring that my brother and I had an incredible education and that there would be nothing to stop us. My father's father would tell my aunt--the one who ended up at McGill University--”You're stronger than 10 men.” For my grandfather to tell this daughter “you're stronger than 10 men”--I mean, this is not even a message that we tell girls now. So this is the lore that I grew up with. A lot of that immigration history is just the traditional, “We sought out an opportunity and we wanted the best for the next generation.”

I think that gives me a real intolerance to being bullied and being mistreated. I think it's part of the reason why I didn't just let this go. My family on both sides worked very hard for me to have the life that I do. And I cannot squander that. That would be completely disrespectful to them and the sacrifices they made. And I mean that for the ancestors I know and for the ancestors I don't know. My ancestors seem to come from places that are not easy, whether it's Kashmir or Lebanon or my enslaved ancestors from Angola. Sierra Leone went through a civil war in the midst of my time in elementary school and definitely during my time in high school. I have cousins who were caught in that and I can see how my life would be different if my father hadn’t chosen to immigrate. I can see how hard those cousins work now that they have immigrated here. Their story and their challenges are different from mine. And they're more similar to my father's. I can see that in real time. So I can't squander this. I can't squander the life that they've all worked hard to give me. I have to fight for the life that I'm worth having. Just because of the color of my skin or just because of my gender doesn't mean that I am not entitled to enjoy this life to the fullest.

Q: It's inspiring to hear you speak with the power of your ancestry behind you and to hear it with such depth. And then to see you laugh in the next moment--I think that that speaks to a lot of resilience honestly.

Dr. Aysha Khoury: I like to keep from crying.

Q: Your heart and your soul is in this, and I see that that's where the laughter comes from, that's where remembering your ancestors come from.

Dr. Aysha Khoury: These have to be very powerful, resilient people. My family who came from Kashmir didn't fly on a plane. There was a whole lot of traveling from land very distant from the ocean. And then there was the ocean. I think about how culturally unique Trinidad and Tobago is across the makeup of the people: both Africans and Indians. When I think about that background it does give me a lot of strength. And it makes me feel very accountable.